本文由阮昕工作室授权mooool发表,欢迎转发,禁止以mooool编辑版本转载。

Thanks to Studio RUAN Xing for authorizing the publication of the project on mooool, Text description provided by Studio RUAN Xing.

阮昕工作室: 围墙可谓中国城市自古以来最重要的空间组织元素之一。但随着中国城市开展史无前例的大规模现代城市化进程,围墙似乎已经被广泛认为是进一步打造“共享”、“开放”城市的阻碍之一。自2016年起,拆除围墙以建设开放街区的理念在中国盛行,但在实践中却碰到了巨大阻力。显然,针对围墙的拆与留并非仅是一个城市和景观设计的问题,而与管理制度、生活方式,甚至是处理物权等法制冲突也密切相关。这个现象不禁引起反思:我们所期待的城市“共享”是否符合当代中国日常生活的习惯和需求呢?

Studio RUAN Xing: Since ancient times, walls have served as one of the most essential means for spatial organizational in Chinese cities. However, with China’s unprecedented large-scale modernization and urbanization, walls have become widely regarded as obstacles to creating “shared” and “open” cities. Since 2016 in China, walls have increasingly been demolished in order to build open neighbourhood. But this move has also encountered significant opposition in practice. The debate over whether to remove or retain walls is not merely about urban and landscape design. It is tied to management systems, way of living, and legal conflicts over property rights. This phenomenon raises the question: does the “sharing” we aspire towards in cities align with the habits and needs of Chinese contemporary daily life?

▽围墙公园,一座墙园,一个园林

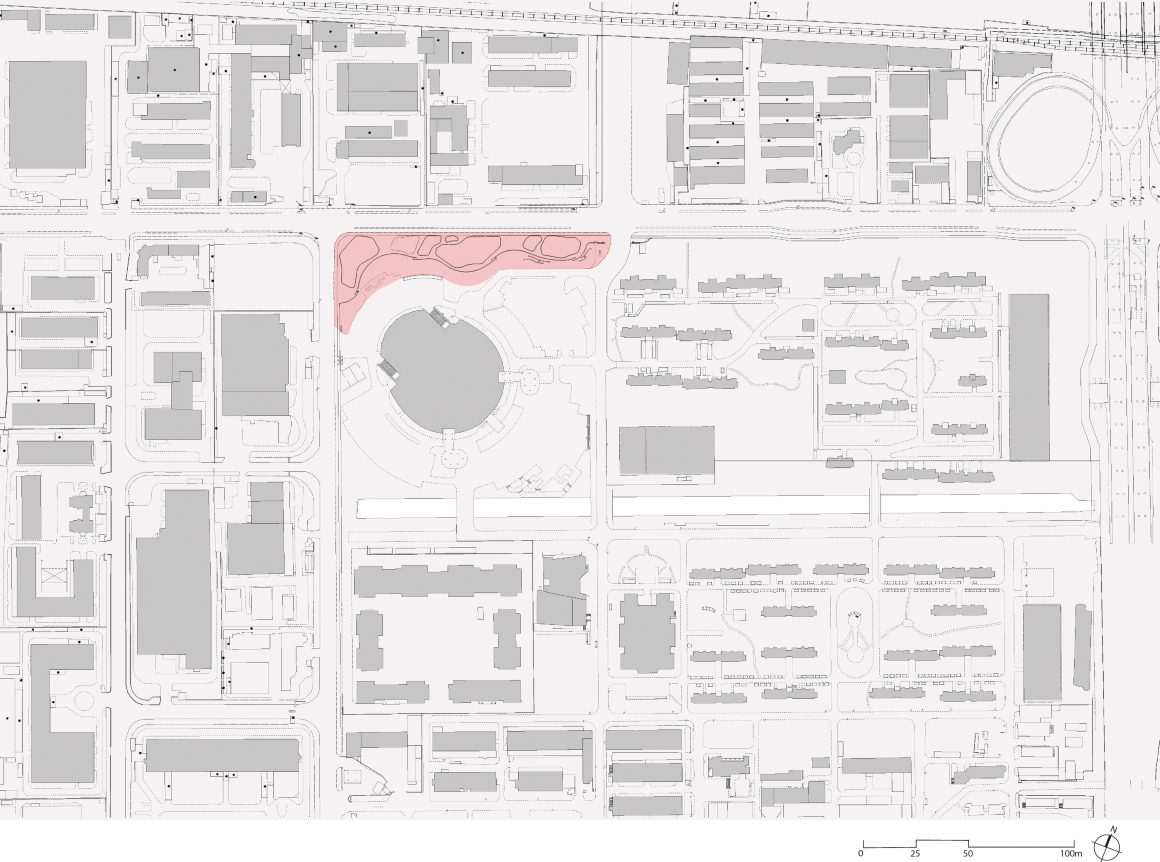

北鲲园地处上海市闵行区上海交通大学北 一 门西侧的剑川路与沧源路交汇处,也是“零号湾——全球创新创业集聚区”的“T字形”区域核心点。该项目所处的“老闵行”是全国建设的第一个工业卫星城,在上世纪60年代曾是城市现代化建设的“新”标杆。伴随着该区域向科创街区转型,闵行区政府与上海交通大学希望将校园内西北角面积约10000平方米,形式“落后”的绿化隔离带改造成为校园与城市共享的“城市公共园林”,再次完成“旧”与“新”的转换。

Beikun Garden is located in Shanghai’s Minhang District, at the intersection of Jianchuan Road and Cangyuan Road, west of Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s North Gate. It is situated at the heart of the “T-shaped” development within the “Zero Bay—Global Innovation and Entrepreneurship Cluster.” The surrounding area, known as “Old Minhang,” was the first industrial satellite city in China, and served as the new benchmark for urban modernization in the 1960s. As the area transitions into a science and innovation district, the Minhang District government and Shanghai Jiao Tong University aim to transform the approximately 10,000-square-meter out-of-date green buffer zone in the campus’s northwest corner into a “urban public garden” for both the campus and the city. In doing so, the hope is to make new out of the “Old” once again.

▽北鲲园总平面图

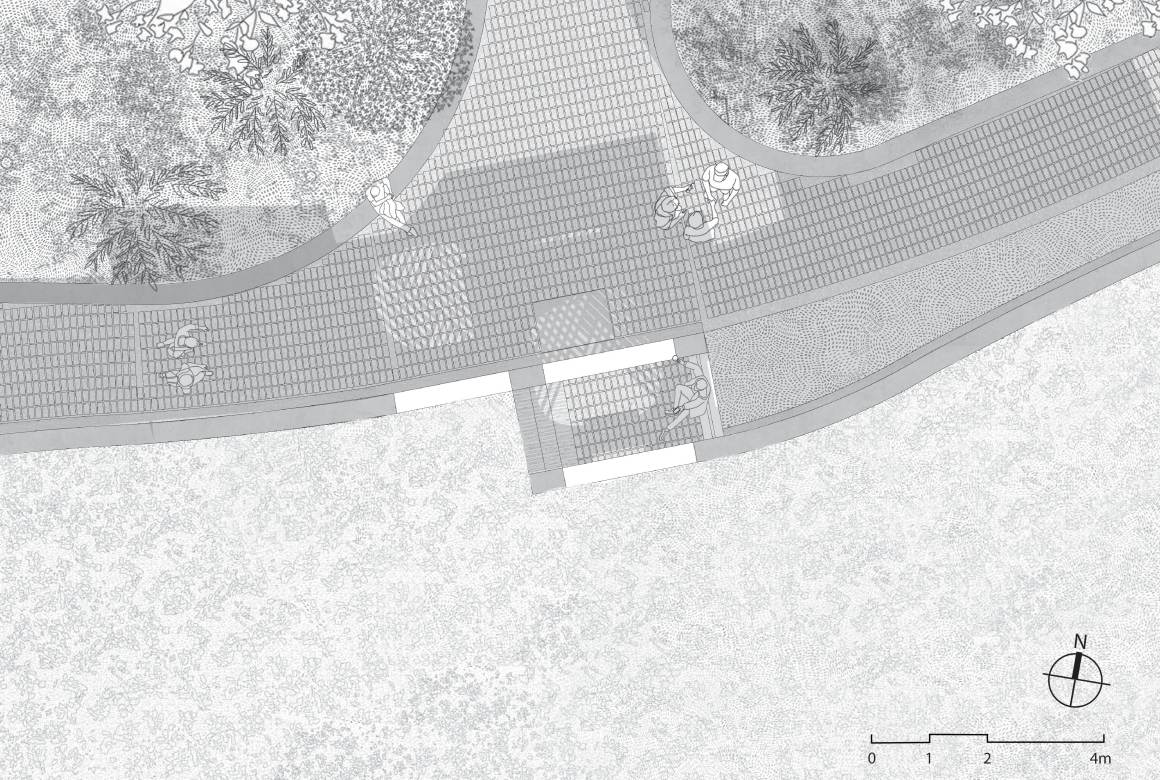

▽北鲲园平面图

但当下的大学校园,尤其是著名大学的校园,仍是一个独立于城市的“单位”,仍需通过明确的边界以确保日常的教学科研秩序而避免沦为“旅游景点”。在面对城市的“开放”与校园的“封闭”这一矛盾时,是否能从时空体验出发,营造相对开放(或封闭)的边界,为围墙的拆与留提出一种具有“相对性”的新选择?因此,北鲲园以“庭园”作为母题,思考“墙”可以为城市提供什么——是一种形式的宣言,是一种人与场所的能动关系,亦或是一种“归隐的权利”。在这个设计中,建筑师希望创造一个可游、可坐的“墙园”,对时空体验的“相对性”给出一种建筑学的回应。

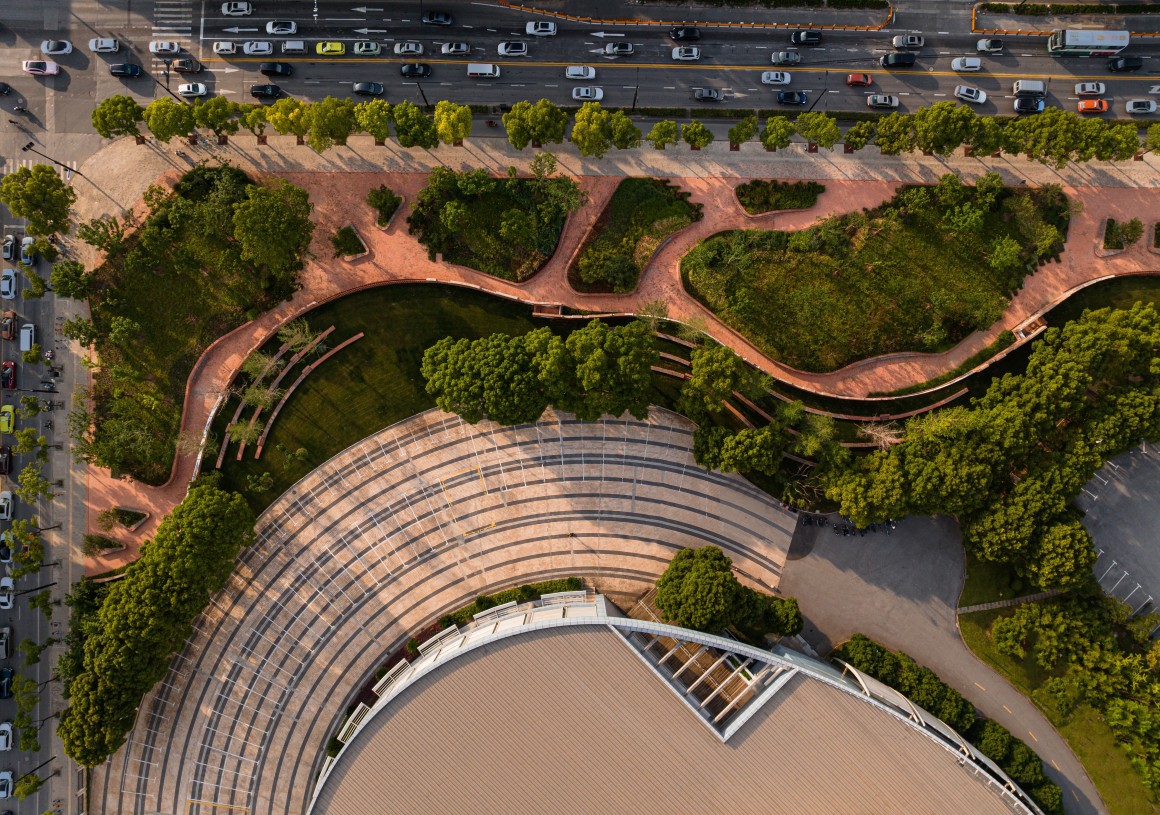

北鲲园的建筑主体为一段东西走向,由五个片段组成,总长约 300 米的墙体。场地仍分为南北两个区域,为校园与城市分别创造视觉相连但又各有特质的多个“庭园”,与核心墙体共同构成一座墙园。

University campuses today, especially those of renowned institutions, still function within cities as independent “work units,” relying on clear boundaries to ensure the daily order of teaching and research and to avoid becoming mere “tourist attractions.” When faced with the tension between a city’s push for “openness” and a campus’s need for “closure,” could we consider a new, relative approach to boundaries, based on spatial and temporal experiences, to provide an alternative to simply demolishing or retaining walls?

In response, Beikun Garden adopts the concept of the “garden court” as its central theme to explore what walls can offer the city—whether as a formal declaration, an animated relationship between people and place, or even as a “right to retreat.” Through this design, the architect aimed to create a “wall garden” with places for sitting and wandering where one can leisurely pass time, offering an architectural response to the “relativity” of spatial and temporal experiences.

The main structure of Beikun Garden is an east-west-oriented wall approximately 300 meters long, composed of five segments. The site remains divided into two areas, north and south respectively, creating several visually connected yet distinct “garden courts” for the campus and the city. Together with the central wall structure, these elements form a cohesive “wall garden.”

▽北鲲园的建筑主体为一段东西走向,由五个片段组成,总长约 300 米的墙体

▽拾级而上的“大庭园”

在归属于校园的南侧区域中,建筑师基于南侧的霍英东体育馆(开学与毕业典礼等重大仪式的举办地),有针对性地补充了可用于仪式聚集和日常交流的空间。墙体与场地中保留下来的一排香樟树围合出三个露天剧场,可以成为毕业庆典后校内师生集体围坐的“大庭园”。在墙中,五个片段的交汇处形成了四个仅可容纳几人日常聚会或个人独处的“小庭园”。

In the southern area, belonging to the campus, the architects designed spaces tailored to the adjacent Henry Fok Gymnasium—a venue for major ceremonies such as semester openings and graduations. They added areas suitable for both ceremonial and informal gatherings. A row of preserved camphor trees, enclosed by the wall and the site layout, forms three amphitheatres. These spaces can serve as a “grand garden court” for faculty and students to gather after graduation.

Within the wall, the intersections of the five segments create four “small garden courts,” each capable of hosting a few people for casual meetings or for their pursuit of personal solitude.

▽“小庭园”平面图

▽北鲲园航拍图

在归属于城市的北侧区域,十四个花池通过具有张力的形体“挤压出”多个小尺度的楔形“庭园”。花池中种植了高而密的景观草而非一般装饰观赏植物,在当下城市大尺度的建筑、街道和广场的夹缝间,营造了稀缺的“柔软”包裹感。这些小尺度的“庭园”适用于休闲或独处,可成为快节奏生活下城市居民谋求“归隐”的庇护所。

部分楔形“庭园”也成为连接道路与墙体的视觉通廊,将来自城市街道的视线导向墙体通透的部分。这个设计的初衷便是在保持校园领域感的同时,打破校园与城市之间围墙的隔绝性,以促进校园内的师生与城市居民在“墙园”中产生互动。因此将墙体设计成为部分“可透视”,使墙内外互动的发生予以能动地“设定”。

In the northern area, which belongs to the city, fourteen plant beds with dynamic forms “compress” space to create multiple small-scale wedge-shaped “garden courts.” Instead of typical ornamental plants, these plant beds are installed with tall and dense ornamental grasses. This design introduces a rare sense of “softness” and enclosure within the gaps of the city’s large-scale buildings, streets, and plazas.

These small-scale “garden courts” are ideal for relaxation or solitude, offering urban residents a sanctuary for “retreat” amidst the fast-paced rhythms of city life.

▽直达花窗的楔形城市“庭园”

▽校园视角下的花格墙

在具体的设计中将“墙园”内的互动方式设定为三种。视觉通廊的终点为两个片段的墙体交叠而成的双层花窗。双层花窗间便是校内“小庭园”,可以与相近尺度的城市“庭园”中的使用者在同一水平高度进行互动。城市“庭园”最开阔处也是墙体最矮处,可成为城市与校园之间沟通最为便利的部分,城市居民的视线可穿过花格墙“透视”校内“庭园”的景致。墙体最实处也是校园内露天剧场的最高处,师生可从“大庭园”拾级而上到达城墙垛口般的顶端凭栏远眺,此时“小庭园”也在不经意间“被发现”。

The design defines three types of interactions within the “wall garden.”At the visual corridors’ endpoints, overlapping segments of the wall form double-layer lattice windows. These lattice layers enclose the campus “small garden courts,” enabling those there to interact on the same level with those in similarly scaled city “garden courts.”

The widest part of the city “garden court,” where the wall is at its lowest, offers the most convenient point of connection between city and campus. Through the brick traceries, urban residents can “peer through” and view the campus “garden courts.”

The most solid part of the wall coincides with the highest point of the amphitheatres within the campus. From the “grand garden court,” faculty and students can ascend steps to the top of the wall, reminiscent of a battlement, and indulge in the distant views. At this moment, the “small garden court” is also serendipitously “discovered.”

▽花窗间的“小庭园”

▽花格墙细部

作为一种形式的“宣言”,北鲲园的细节设计体现了建筑师对建筑时间“相对性”的反思。作为一个城市更新项目,北鲲园呈现了一种近似“古迹”的质感,比更新以前显得“更旧”了。北鲲园所采用的“罗马砖”体现的是建筑师希望对建筑“老去”后的状态进行设计。“冗余”的砂浆填缝保证大多数的砖均为统一尺寸且不被切割,表面的黑斑保留了不充分燃烧产生的“瑕疵”。墙上的铜牌与座椅的木料均未涂刷保护层,以期通过材料的变化记录时间,并与周围茁壮的景观草传递自然在建筑上留下的原始力量。

As a form of “declaration,” the detailed design of Beikun Garden reflects the architect’s consideration of the “relativity” of architecture and time. As a project of urban renewal, Beikun Garden makes use of a texture resembling that of “ruins.” It appears “older” than it did before the renewal.

The use of “Roman bricks” showcases the architect’s intention to make the wall appear old. The “excessive” mortar joints ensure that most bricks retain a uniform size without being cut, while the black spots on the surface preserve the “imperfections” caused by incomplete firing.

The brass plaques on the walls and the timber used for seating are left untreated, allowing the passage of time to be imprinted through the weathering of the material. Together with the robust ornamental grass that surrounds, the raw power of nature imprinted on architecture resonates.

▽栏杆上的光影与记录校史的铜牌

与一般的红砖建筑不同,北鲲园的“粗粝”质感并非是追求一种复古的风格,而是衬托“精致”(如栏杆和铜牌)。尽管中国建筑在过去的三千年中仅有“院落”一种母题,但在持续稳定的空间内却诞生了繁荣而永续的中华文化。“新”与“旧”既是对立的也是相对的。建筑在中国文化中的作用并非来自其“脆薄”的物质性与风格,而源于对生活方式产生的支撑作用,即是将“院落”发展成为场地空间多变并富有生活情趣的“庭园”。当身处城市“庭园”并立于墙前时,“精致“的铜牌在“粗粝“的墙体衬托下自然而然地吸引了人的感官,使之如同传统建筑的匾额般以文本的方式直截了当地记录并呈现了上海交大的辉煌校史。这亦是从城市“庭园”对校园进行一种抽象的“透视”:阅读大学的文化与内涵。

Unlike typical red brick buildings, Beikun Garden’s “coarse” texture does not aspire towards a retro style. Instead it serves to highlight “refinement” (such as through railings and brass plaques). Although Chinese architecture has only one central theme—”the courtyard”—over the past three thousand years, it has given birth to a prosperous and enduring Chinese culture within a stable and continuous spatial context. “New” and “old” are both opposites and relative concepts.

In Chinese culture, the role of architecture does not stem from its “fragile” materiality or style, but from the supportive role it plays in everyday life. It is about transforming a “courtyard” into a place both dynamic and full of life, evolving into a “garden court.”

When standing in the urban “garden court” and facing the wall, the “refined” brass plaques effortlessly draw attention thanks to their contrast with the “rough” wall, much like traditional architectural plaques. They directly record and present the glorious history of Shanghai Jiao Tong University in textual form. This also offers an abstract “perspective” of the campus from the city “garden court,” inviting a reading of the university’s culture and its content.

北鲲园位于上海交大西北角,取名来自庄子:回应该园取名“北鲲”,庄子在《逍遥游》中即是以寓言的方式对“相对性”予以诠释,而建筑师则在设计探讨了墙所蕴含的悖论。“无用”与“有用”既是对立的也是相对的。建筑师看似“无用”地再造了一堵“古迹”般的围墙,实则“有用”地用一座“墙园”介入到校园与城市之间的活动中,从而营造了校园的“相对开放性”:既让校园面向城市呈现了一种特殊的开放姿态,同时又保持了高校日常运营所必须的独立性。这是大学必须保持的一种仰望星空的理想,即“象牙塔”的真正含义。

Beikun Garden is located at the northwest corner of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and its name is derived from a passage in the Zhuangzi:Turning back to the garden’s name “Beikun,” in this passage Zhuangzi uses allegory to interpret the concept of “relativity.” The architects, in their design, explore the paradox contained within the walls. “Useless” and “useful” are both opposites and relative concepts.

The architect and seemingly “uselessly” recreates a wall that resembles a “ruin,” but in reality, he “usefully” introduces a “wall garden” that mediates between campus and city, creating a “relative openness” for the campus. This design allows the campus to present a unique form of openness to the city while maintaining the independence essential for the university’s daily functions. This represents the ideal that a university must uphold—looking up to the stars, and embodying the true meaning of the “ivory tower.”

▽花窗和树影

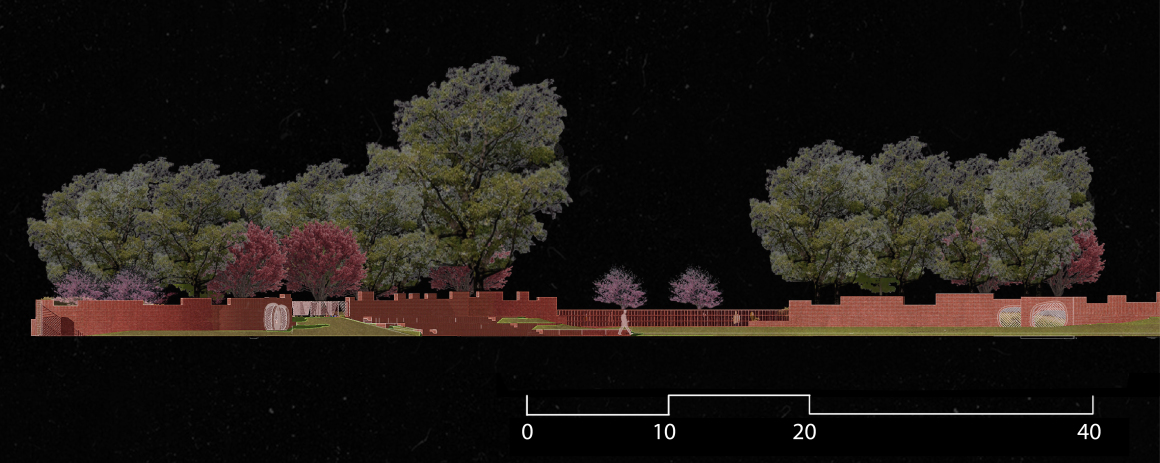

▽校园区域立面图城市区域立面图

“ 用一座“墙园”介入到校园与城市之间的活动中,从而营造了校园的“相对开放性”。”

审稿编辑:junjun

更多 Read more about:阮昕工作室

0 Comments